Charles Piazzi Smyth on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Charles Piazzi Smyth (3 January 1819 – 21 February 1900) was an Italian-born British astronomer who was Astronomer Royal for Scotland from 1846 to 1888; he is known for many innovations in

In 1704

In 1704  The dust was evidently confined to individual layers, so he decided to move to Alta Vista at , on the eastern slope of Teide, the highest point that mules could reach. He was determined to use the larger Pattinson telescope and returned to

The dust was evidently confined to individual layers, so he decided to move to Alta Vista at , on the eastern slope of Teide, the highest point that mules could reach. He was determined to use the larger Pattinson telescope and returned to

Smyth subsequently published his book ''Our Inheritance in the Great Pyramid'' in 1864 (which he expanded over the years and is also titled ''The Great Pyramid: Its Secrets and Mysteries Revealed''). Smyth claimed that the measurements he obtained from the Great Pyramid of Giza indicated a unit of length, the

Smyth subsequently published his book ''Our Inheritance in the Great Pyramid'' in 1864 (which he expanded over the years and is also titled ''The Great Pyramid: Its Secrets and Mysteries Revealed''). Smyth claimed that the measurements he obtained from the Great Pyramid of Giza indicated a unit of length, the

In 1855 Smyth married Jessica "Jessie" Duncan (1812–1896), daughter of Thomas Duncan. Jessie Duncan was a geologist who had studied with Alexander Rose in Edinburgh, and travelled on geological expeditions to Ireland, France, Switzerland and Italy.

Smyth's brothers were

In 1855 Smyth married Jessica "Jessie" Duncan (1812–1896), daughter of Thomas Duncan. Jessie Duncan was a geologist who had studied with Alexander Rose in Edinburgh, and travelled on geological expeditions to Ireland, France, Switzerland and Italy.

Smyth's brothers were

Honorary Members and Fellows

/ref> The crater Piazzi Smyth on the

Full text available from

Full text available

on the

Full text available from

Google Books *

Full text available from

Google Books * *

Critical comments

on some of Smyth's books, by Olin J. Eggen (1955). * * * *

* * ttp://www.greatdreams.com/pyramid.htm Pyramidology – A Case of Science, Pseudo-science and Religion

Charles Piazzi Smyth, ''Our Inheritance in the Great Pyramid'' (1877) Plate Index

* ttp://www.catchpenny.org/pyramid.html Amazing Pyramid "Facts"

B-P's Uncle: Charles Piazzi Smyth

The Astronomical Society of Edinburgh: A Guide to Edinburgh's Popular Observatory

* ttp://www.leeds.ac.uk/cath/events/2003/1205/programme.html "The Sphinx and the Great Pyramid at Giza, 1865" photograph by Smyth

The Royal Observatory, Edinburgh

{{DEFAULTSORT:Smyth, Charles Piazzi 1819 births 1900 deaths 19th-century English writers 19th-century apocalypticists 19th-century writers on archaeological subjects Academics of the University of Edinburgh Alumni of the University of Edinburgh 19th-century British astronomers British Israelism 19th-century Neapolitan people Fellows of the Royal Astronomical Society Fellows of the Royal Society Fellows of the Royal Society of Edinburgh People educated at Bedford School Pyramidologists Victorian writers Great Pyramid of Giza

astronomy

Astronomy () is a natural science that studies astronomical object, celestial objects and phenomena. It uses mathematics, physics, and chemistry in order to explain their origin and chronology of the Universe, evolution. Objects of interest ...

and, along with his wife Jessica Duncan Piazzi Smyth, his pyramidological and metrological

Metrology is the scientific study of measurement. It establishes a common understanding of units, crucial in linking human activities. Modern metrology has its roots in the French Revolution's political motivation to standardise units in Fra ...

studies of the Great Pyramid of Giza

The Great Pyramid of Giza is the biggest Egyptian pyramid and the tomb of Fourth Dynasty pharaoh Khufu. Built in the early 26th century BC during a period of around 27 years, the pyramid is the oldest of the Seven Wonders of the Ancient World, ...

.

Astronomical career

Charles Piazzi Smyth (pronounced ) was born inNaples

Naples (; it, Napoli ; nap, Napule ), from grc, Νεάπολις, Neápolis, lit=new city. is the regional capital of Campania and the third-largest city of Italy, after Rome and Milan, with a population of 909,048 within the city's adminis ...

, Italy, to Captain (later Admiral) William Henry Smyth

Admiral William Henry Smyth (21 January 1788 – 8 September 1865) was a Royal Navy officer, hydrographer, astronomer and numismatist. He is noted for his involvement in the early history of a number of learned societies, for his hydrographic ...

and his wife Annarella. He was named Piazzi after his godfather, the Italian astronomer Giuseppe Piazzi

Giuseppe Piazzi ( , ; 16 July 1746 – 22 July 1826) was an Italian Catholic priest of the Theatine order, mathematician, and astronomer. He established an observatory at Palermo, now the '' Osservatorio Astronomico di Palermo – Giuseppe ...

, whose acquaintance his father had made at Palermo

Palermo ( , ; scn, Palermu , locally also or ) is a city in southern Italy, the capital (political), capital of both the autonomous area, autonomous region of Sicily and the Metropolitan City of Palermo, the city's surrounding metropolitan ...

when serving in the Mediterranean

The Mediterranean Sea is a sea connected to the Atlantic Ocean, surrounded by the Mediterranean Basin and almost completely enclosed by land: on the north by Western and Southern Europe and Anatolia, on the south by North Africa, and on the e ...

. His father subsequently settled at Bedford

Bedford is a market town in Bedfordshire, England. At the 2011 Census, the population of the Bedford built-up area (including Biddenham and Kempston) was 106,940, making it the second-largest settlement in Bedfordshire, behind Luton, whilst ...

and equipped there an observatory

An observatory is a location used for observing terrestrial, marine, or celestial events. Astronomy, climatology/meteorology, geophysical, oceanography and volcanology are examples of disciplines for which observatories have been constructed. His ...

, at which Piazzi Smyth received his first lessons in astronomy. He was educated at Bedford School

:''Bedford School is not to be confused with Bedford Girls' School, Bedford High School, Bedford Modern School, Old Bedford School in Bedford, Texas or Bedford Academy in Bedford, Nova Scotia.''

Bedford School is a public school (English indep ...

until the age of sixteen when he became an assistant to Sir Thomas Maclear

Sir Thomas Maclear (17 March 1794 – 14 July 1879) was an Irish-born South African astronomer who became Her Majesty's astronomer at the Cape of Good Hope.

Life

He was born in Newtownstewart, County Tyrone, Ireland, the eldest son of Rev Jam ...

at the Cape of Good Hope

The Cape of Good Hope ( af, Kaap die Goeie Hoop ) ;''Kaap'' in isolation: pt, Cabo da Boa Esperança is a rocky headland on the Atlantic coast of the Cape Peninsula in South Africa.

A common misconception is that the Cape of Good Hope is t ...

, where he observed

Halley's comet

Halley's Comet or Comet Halley, officially designated 1P/Halley, is a short-period comet visible from Earth every 75–79 years. Halley is the only known short-period comet that is regularly visible to the naked eye from Earth, and thus the o ...

and the Great Comet of 1843

The Great Comet of 1843, formally designated C/1843 D1 and 1843 I, was a long-period comet which became very bright in March 1843 (it is also known as the Great March Comet). It was discovered on February 5, 1843, and rapidly brightened to beco ...

, and took an active part in the verification and extension of Nicolas Louis de Lacaille

Abbé Nicolas-Louis de Lacaille (; 15 March 171321 March 1762), formerly sometimes spelled de la Caille, was a French astronomer and geodesist who named 14 out of the 88 constellations. From 1750 to 1754, he studied the sky at the Cape of Good ...

's arc of the meridian

In geodesy and navigation, a meridian arc is the curve between two points on the Earth's surface having the same longitude. The term may refer either to a segment of the meridian, or to its length.

The purpose of measuring meridian arcs is to ...

.

In 1846 he was appointed Astronomer Royal for Scotland, based at the Calton Hill Observatory in Edinburgh

Edinburgh ( ; gd, Dùn Èideann ) is the capital city of Scotland and one of its 32 Council areas of Scotland, council areas. Historically part of the county of Midlothian (interchangeably Edinburghshire before 1921), it is located in Lothian ...

, and professor of astronomy in the University of Edinburgh

The University of Edinburgh ( sco, University o Edinburgh, gd, Oilthigh Dhùn Èideann; abbreviated as ''Edin.'' in post-nominals) is a public research university based in Edinburgh, Scotland. Granted a royal charter by King James VI in 15 ...

. Shortly after his appointment, the observatory was placed under the control of Her Majesty's Treasury

His Majesty's Treasury (HM Treasury), occasionally referred to as the Exchequer, or more informally the Treasury, is a department of His Majesty's Government responsible for developing and executing the government's public finance policy and e ...

and suffered from a long series of under-funding. Because of this, most of his notable work in astronomy was done elsewhere. Here he completed the reduction, and continued the series, of the observations made by his predecessor, Thomas James Henderson

Thomas Henderson FRSE FRS FRAS (28 December 1798 – 23 November 1844) was a Scottish astronomer and mathematician noted for being the first person to measure the distance to Alpha Centauri, the major component of the nearest stellar syste ...

. In 1853, Smyth was responsible for installing the time ball

A time ball or timeball is a time-signalling device. It consists of a large, painted wooden or metal ball that is dropped at a predetermined time, principally to enable navigators aboard ships offshore to verify the setting of their marine chron ...

on top of Nelson's Monument in Edinburgh to give a time signal to the ships at Edinburgh's port of Leith

Leith (; gd, Lìte) is a port area in the north of the city of Edinburgh, Scotland, founded at the mouth of the Water of Leith. In 2021, it was ranked by '' Time Out'' as one of the top five neighbourhoods to live in the world.

The earliest ...

. By 1861, this visual signal was augmented by the One O'Clock Gun

Edinburgh Castle is a historic castle in Edinburgh, Scotland. It stands on Castle Rock, which has been occupied by humans since at least the Iron Age, although the nature of the early settlement is unclear. There has been a royal castle on t ...

at Edinburgh Castle

Edinburgh Castle is a historic castle in Edinburgh, Edinburgh, Scotland. It stands on Castle Rock (Edinburgh), Castle Rock, which has been occupied by humans since at least the Iron Age, although the nature of the early settlement is unclear. ...

.

In 1704

In 1704 Isaac Newton

Sir Isaac Newton (25 December 1642 – 20 March 1726/27) was an English mathematician, physicist, astronomer, alchemist, theologian, and author (described in his time as a "natural philosopher"), widely recognised as one of the grea ...

wrote in his book Opticks

''Opticks: or, A Treatise of the Reflexions, Refractions, Inflexions and Colours of Light'' is a book by English natural philosopher Isaac Newton that was published in English in 1704 (a scholarly Latin translation appeared in 1706). (''Optick ...

Book 1, Part 1:

"... elescopes... cannot be so formed as to take away that confusion of the Rays which arises from the Tremors of the Atmosphere. The only Remedy is a most serene and quiet Air, such as may perhaps be found on the tops of the highest Mountains above the grosser Clouds." This suggestion fell on deaf ears until in 1856, Smyth petitioned the Admiralty

Admiralty most often refers to:

*Admiralty, Hong Kong

*Admiralty (United Kingdom), military department in command of the Royal Navy from 1707 to 1964

*The rank of admiral

*Admiralty law

Admiralty can also refer to:

Buildings

* Admiralty, Traf ...

for a grant of £500 to take a telescope to the slopes of Teide

Teide, or Mount Teide, ( es, El Teide, Pico del Teide, , "Peak of Teide") is a volcano on Tenerife in the Canary Islands, Spain. Its summit (at ) is the highest point in Spain and the highest point above sea level in the islands of the Atlan ...

in Tenerife

Tenerife (; ; formerly spelled ''Teneriffe'') is the largest and most populous island of the Canary Islands. It is home to 43% of the total population of the archipelago. With a land area of and a population of 978,100 inhabitants as of Janu ...

(which he spelt Teneriffe) and test whether Newton had been right or not. In South Africa he had spent many nights observing from mountain tops but when he moved to Edinburgh had been appalled by the poor observing conditions there.

The Admiralty approved his grant and he was offered the loan of further equipment from many sources. Robert Stephenson

Robert Stephenson Fellow of the Royal Society, FRS HFRSE FRSA Doctor of Civil Law, DCL (16 October 1803 – 12 October 1859) was an English civil engineer and designer of locomotives. The only son of George Stephenson, the "Father of Railway ...

loaned his 140-ton yacht "Titania" for the expedition. Mr. Hugh Pattinson loaned his refracting telescope

A refracting telescope (also called a refractor) is a type of optical telescope that uses a lens (optics), lens as its objective (optics), objective to form an image (also referred to a dioptrics, dioptric telescope). The refracting telescope d ...

of . This was a Thomas Cooke equatorial with setting circles and a driving clock. The Crimean War

The Crimean War, , was fought from October 1853 to February 1856 between Russia and an ultimately victorious alliance of the Ottoman Empire, France, the United Kingdom and Piedmont-Sardinia.

Geopolitical causes of the war included the de ...

had recently concluded and the army offered to lend tents. This offer was declined as Piazzi Smyth had already designed a tent with a sewn-in groundsheet based on his experience in South Africa.

On this and all his subsequent trips he was accompanied by his wife whom he had married the year before. In 1856, on reaching Tenerife they first set up camp on Mount Guajara

Mount Guajara is a high mountain on Tenerife, in the Canary Islands. It is the third altitude of the island and of the Canary archipelago, after Teide and Pico Viejo.

Mount Guajara along with the entire Island of Tenerife is dormant volcano whi ...

, a peak about south of Teide (all heights on Tenerife are those he derived barometrically). It was higher than all its neighbours and free from any volcanic activity. They took all their equipment up loaded on mules, except for the Pattinson telescope which was much too bulky. They stayed there a month making astronomical, meteorological and geological observations. He made observations of the steadiness and clarity of star images with the 3.6-inch (9 cm) Sheepshanks telescope and found both much better than at Edinburgh. He also made the first positive detection of heat coming from the Moon

The Moon is Earth's only natural satellite. It is the fifth largest satellite in the Solar System and the largest and most massive relative to its parent planet, with a diameter about one-quarter that of Earth (comparable to the width of ...

. However, they were annoyed by frequent dust incursions which frequently blotted out the horizon. Even when the dust was at its worst, the transparency at the zenith was better than at Edinburgh.

The dust was evidently confined to individual layers, so he decided to move to Alta Vista at , on the eastern slope of Teide, the highest point that mules could reach. He was determined to use the larger Pattinson telescope and returned to

The dust was evidently confined to individual layers, so he decided to move to Alta Vista at , on the eastern slope of Teide, the highest point that mules could reach. He was determined to use the larger Pattinson telescope and returned to La Orotava

La Orotava is a town and a municipality in the northern part of Tenerife, one of the Canary Islands of Spain. The area of the municipality stretches from the north coast to the mountainous interior, and includes the summit of the Teide volcano, ...

to fetch it. As the three boxes were too heavy, they were opened and the contents distributed among several smaller boxes which were loaded on to seven strong horses. The telescope was soon mounted and in action. The Airy Disc

In optics, the Airy disk (or Airy disc) and Airy pattern are descriptions of the best- focused spot of light that a perfect lens with a circular aperture can make, limited by the diffraction of light. The Airy disk is of importance in physics, ...

was clearly seen and he made many critical observations and fine drawings. They spent a month there during which they spent a day climbing to the summit of Teide at .

The scientific results were described in reports addressed to the Lord Commissioners of the Admiralty

This is a list of Lords Commissioners of the Admiralty (incomplete before the Restoration, 1660).

The Lords Commissioners of the Admiralty were the members of The Board of Admiralty, which exercised the office of Lord High Admiral when it was n ...

, the Royal Society

The Royal Society, formally The Royal Society of London for Improving Natural Knowledge, is a learned society and the United Kingdom's national academy of sciences. The society fulfils a number of roles: promoting science and its benefits, re ...

, and the "Astronomical Observations made at the Royal Observatory, Edinburgh Vol XII 1863", which were widely acclaimed. Piazzi Smyth was the pioneer of the modern practice of placing telescopes at high altitudes to enjoy the best observing conditions.

He wrote a popular account of the voyage in "Teneriffe, an astronomers Experiment". This was the first book ever illustrated by stereoscopic photographs ("photo-stereographs"). It included 20 stereoviews of Teneriffe taken by the author using the wet collodion process. A stereoscope could be purchased which allowed the pictures to be viewed in 3-D without removing them from the book.

In 1871 and 1872 Smyth investigated the spectra of the aurora

An aurora (plural: auroras or aurorae), also commonly known as the polar lights, is a natural light display in Earth's sky, predominantly seen in high-latitude regions (around the Arctic and Antarctic). Auroras display dynamic patterns of bri ...

, and zodiacal light

The zodiacal light (also called false dawn when seen before sunrise) is a faint glow of diffuse sunlight scattered by interplanetary dust. Brighter around the Sun, it appears in a particularly dark night sky to extend from the Sun's direction in ...

. He recommended the use of the rain-band for weather forecasting

Weather forecasting is the application of science and technology forecasting, to predict the conditions of the Earth's atmosphere, atmosphere for a given location and time. People have attempted to predict the weather informally for millennia a ...

and discovered, in conjunction with Alexander Stewart Herschel

Alexander Stewart Herschel, DCL, FRS (5 February 1836 – 18 June 1907) was a British astronomer.

Although much less well known than his grandfather William Herschel or his father John Herschel, he did pioneering work in meteor spectroscopy. ...

, the harmonic relation between the rays emitted by carbon monoxide

Carbon monoxide (chemical formula CO) is a colorless, poisonous, odorless, tasteless, flammable gas that is slightly less dense than air. Carbon monoxide consists of one carbon atom and one oxygen atom connected by a triple bond. It is the simple ...

. In 1877–1878 he constructed at Lisbon

Lisbon (; pt, Lisboa ) is the capital and largest city of Portugal, with an estimated population of 544,851 within its administrative limits in an area of 100.05 km2. Grande Lisboa, Lisbon's urban area extends beyond the city's administr ...

a map of the solar spectrum

A spectrum (plural ''spectra'' or ''spectrums'') is a condition that is not limited to a specific set of values but can vary, without gaps, across a continuum. The word was first used scientifically in optics to describe the rainbow of colors i ...

for which he received the Makdougall Brisbane Prize

The Royal Society of Edinburgh is Scotland's national academy of science and letters. It is a registered charity that operates on a wholly independent and non-partisan basis and provides public benefit throughout Scotland. It was established i ...

in 1880. Smyth carried out further spectroscopic

Spectroscopy is the field of study that measures and interprets the electromagnetic spectra that result from the interaction between electromagnetic radiation and matter as a function of the wavelength or frequency of the radiation. Matter wa ...

researches at Madeira

)

, anthem = ( en, "Anthem of the Autonomous Region of Madeira")

, song_type = Regional anthem

, image_map=EU-Portugal_with_Madeira_circled.svg

, map_alt=Location of Madeira

, map_caption=Location of Madeira

, subdivision_type=Sovereign st ...

in 1880 and at Winchester

Winchester is a City status in the United Kingdom, cathedral city in Hampshire, England. The city lies at the heart of the wider City of Winchester, a local government Districts of England, district, at the western end of the South Downs Nation ...

in 1884.

In 1888 Smyth resigned as Astronomer Royal in protest at the chronic under-funding and age of his equipment. This brought events to a head and the Royal Observatory was almost closed when James Lindsay, Earl of Crawford made a donation of new astronomical instruments and the complete ''Bibliotheca Lindesiana'' in order that a new observatory could be founded. Thanks to this donation, the new Royal Observatory on Blackford Hill

Blackford Hill is a hill in Edinburgh, the capital city of Scotland. It is in the area of Blackford, between Morningside, and the Braid Hills. Together with the Hermitage of Braid, it comprises the Hermitage of Braid and Blackford Hill Loca ...

was opened in 1896. After his resignation, Smyth retired to the neighbourhood of Ripon

Ripon () is a cathedral city in the Borough of Harrogate, North Yorkshire, England. The city is located at the confluence of two tributaries of the River Ure, the Laver and Skell. Historically part of the West Riding of Yorkshire, the city ...

, where he remained until his death.

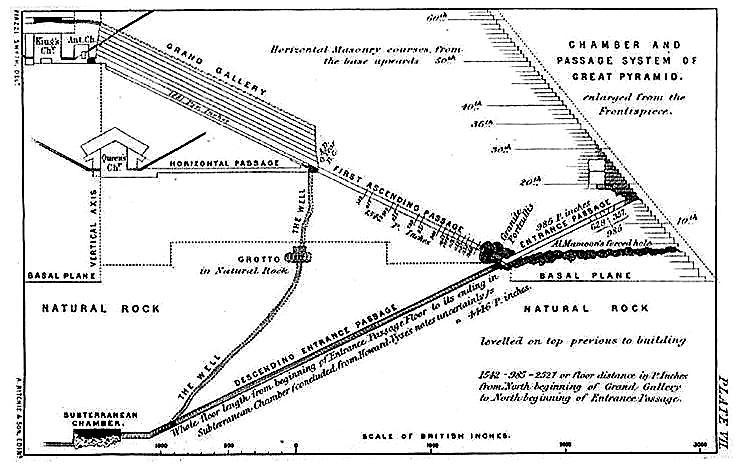

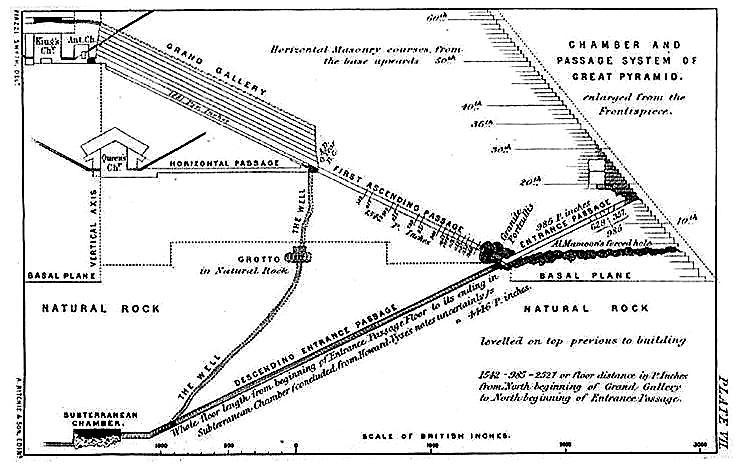

Pyramidological researches

Smyth corresponded with pyramid theorist John Taylor and was heavily influenced by him. Taylor theorized in his 1859 book ''The Great Pyramid: Why Was It Built? & Who Built It?'' that the Great Pyramid was planned and the building supervised by thebiblical

The Bible (from Koine Greek , , 'the books') is a collection of religious texts or scriptures that are held to be sacred in Christianity, Judaism, Samaritanism, and many other religions. The Bible is an anthologya compilation of texts of a ...

Noah

Noah ''Nukh''; am, ኖህ, ''Noḥ''; ar, نُوح '; grc, Νῶε ''Nôe'' () is the tenth and last of the pre-Flood patriarchs in the traditions of Abrahamic religions. His story appears in the Hebrew Bible (Book of Genesis, chapters 5– ...

. Refused a grant by the Royal Society, Smyth went on an expedition to Egypt in order to accurately measure every surface, dimension, and aspect of the Great Pyramid. He brought along equipment to measure the dimensions of the stones, the precise angle of sections such as the descending passage, and a specially designed camera

A camera is an Optics, optical instrument that can capture an image. Most cameras can capture 2D images, with some more advanced models being able to capture 3D images. At a basic level, most cameras consist of sealed boxes (the camera body), ...

to photograph both the interior and exterior of the pyramid. He also used other instruments to make astronomical calculations and determine the pyramid's accurate latitude and longitude.

Smyth subsequently published his book ''Our Inheritance in the Great Pyramid'' in 1864 (which he expanded over the years and is also titled ''The Great Pyramid: Its Secrets and Mysteries Revealed''). Smyth claimed that the measurements he obtained from the Great Pyramid of Giza indicated a unit of length, the

Smyth subsequently published his book ''Our Inheritance in the Great Pyramid'' in 1864 (which he expanded over the years and is also titled ''The Great Pyramid: Its Secrets and Mysteries Revealed''). Smyth claimed that the measurements he obtained from the Great Pyramid of Giza indicated a unit of length, the pyramid inch

The pyramid inch is a unit of measure claimed by pyramidologists to have been used in ancient times.

History

The first suggestion that the builders of the Great Pyramid of Giza used units of measure related to modern measures is attributed to O ...

, equivalent to 1.001 British

British may refer to:

Peoples, culture, and language

* British people, nationals or natives of the United Kingdom, British Overseas Territories, and Crown Dependencies.

** Britishness, the British identity and common culture

* British English, ...

inches, that could have been the standard of measurement by the pyramid's architects. From this he extrapolated a number of other measurements, including the pyramid pint

The pint (, ; symbol pt, sometimes abbreviated as ''p'') is a unit of volume or capacity in both the imperial unit, imperial and United States customary units, United States customary measurement systems. In both of those systems it is tradition ...

, the sacred cubit

The cubit is an ancient unit of length based on the distance from the elbow to the tip of the middle finger. It was primarily associated with the Sumerians, Egyptians, and Israelites. The term ''cubit'' is found in the Bible regarding No ...

, and the pyramid scale of temperature

Scale of temperature is a methodology of calibrating the physical quantity temperature in metrology. Empirical scales measure temperature in relation to convenient and stable parameters, such as the freezing and boiling point of water. Absolut ...

.

Smyth claimed that the pyramid inch was a God-given measure handed down through the centuries from the time of Shem (Noah's Son), and that the architects of the pyramid could only have been directed by the hand of God. To support this Smyth said that, in measuring the pyramid, he found the number of inches in the perimeter of the base equalled one hundred times the number of days in a year, and found a numeric relationship between the height of the pyramid in inches to the distance from Earth to the Sun, measured in statute miles. He also advanced the theory that the Great Pyramid was a repository of prophecies

In religion, a prophecy is a message that has been communicated to a person (typically called a ''prophet'') by a supernatural entity. Prophecies are a feature of many cultures and belief systems and usually contain divine will or law, or prete ...

which could be revealed by detailed measurements of the structure. Working upon theories by Taylor, he conjectured that the Hyksos

Hyksos (; Egyptian '' ḥqꜣ(w)- ḫꜣswt'', Egyptological pronunciation: ''hekau khasut'', "ruler(s) of foreign lands") is a term which, in modern Egyptology, designates the kings of the Fifteenth Dynasty of Egypt (fl. c. 1650–1550 BC).

T ...

were the Hebrew people

The terms ''Hebrews'' (Hebrew: / , Modern: ' / ', Tiberian: ' / '; ISO 259-3: ' / ') and ''Hebrew people'' are mostly considered synonymous with the Semitic-speaking Israelites, especially in the pre-monarchic period when they were still n ...

, and that they built the Great Pyramid under the leadership of Melchizedek

In the Bible, Melchizedek (, hbo, , malkī-ṣeḏeq, "king of righteousness" or "my king is righteousness"), also transliterated Melchisedech or Malki Tzedek, was the king of Salem and priest of (often translated as "most high God"). He is f ...

. Because the pyramid inch was a divine unit of measurement, Smyth, a committed proponent of British Israelism

British Israelism (also called Anglo-Israelism) is the British nationalist, pseudoarchaeological, pseudohistorical and pseudoreligious belief that the people of Great Britain are "genetically, racially, and linguistically the direct descendant ...

, used his conclusions as an argument against the introduction of the metric system

The metric system is a system of measurement that succeeded the Decimal, decimalised system based on the metre that had been introduced in French Revolution, France in the 1790s. The historical development of these systems culminated in the d ...

in Britain. For much of his life he was a vocal opponent of the metric system, which he considered a product of the minds of atheistic French radicals, a position advocated in many of his works.

Smyth, despite his bad reputation in Egyptological

Egyptology (from ''Egypt'' and Greek , ''-logia''; ar, علم المصريات) is the study of ancient Egyptian history, language, literature, religion, architecture and art from the 5th millennium BC until the end of its native religious p ...

circles today, performed much valuable work at Giza. He made the most accurate measurements of the Great Pyramid that any explorer had made up to that time, and he photographed the interior passages, using a magnesium

Magnesium is a chemical element with the symbol Mg and atomic number 12. It is a shiny gray metal having a low density, low melting point and high chemical reactivity. Like the other alkaline earth metals (group 2 of the periodic ta ...

light, for the first time. Smyth's work resulted in many drawings and calculations, which were soon incorporated into his books ''Our Inheritance in the Great Pyramid'', the three-volume ''Life and Work at the Great Pyramid'' (1867), and ''On the Antiquity of Intellectual Man'' (1868). For his works he was awarded the Keith gold medal for 1865–67 by the Royal Society of Edinburgh

The Royal Society of Edinburgh is Scotland's national academy of science and letters. It is a registered charity that operates on a wholly independent and non-partisan basis and provides public benefit throughout Scotland. It was established i ...

, but in 1874, the Royal Society of London

The Royal Society, formally The Royal Society of London for Improving Natural Knowledge, is a learned society and the United Kingdom's national academy of sciences. The society fulfils a number of roles: promoting science and its benefits, re ...

rejected his paper on the design of Khufu's pyramid, as they had Taylor's. The rejection of his ideas helped contribute to his resignation from his post as Royal Astronomer in 1888.

Influence of Smyth's pyramid theories

Smyth's theories on pyramid prophecy were then integrated into the works and prophecies ofCharles Taze Russell

Charles Taze Russell (February 16, 1852 – October 31, 1916), or Pastor Russell, was an American Christian restorationist minister from Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, and founder of what is now known as the Bible Student movement. He was an ...

(such as his ''Studies in the Scriptures

''Studies in the Scriptures'' is a series of publications, intended as a Bible study aid, containing seven volumes of great importance to the history of the Bible Student movement, and the early history of Jehovah's Witnesses.

Origin

The author o ...

''), who founded the Bible Student movement

The Bible Student movement is a Millennialist Restorationist Christian movement. It emerged from the teachings and ministry of Charles Taze Russell (1852–1916), also known as Pastor Russell, and his founding of the Zion's Watch Tower Tract S ...

(who adopted the name Jehovah's Witnesses

Jehovah's Witnesses is a millenarian restorationist Christian denomination with nontrinitarian beliefs distinct from mainstream Christianity. The group reports a worldwide membership of approximately 8.7 million adherents involved in ...

in 1931, though Russell's successor, Joseph F. Rutherford, denounced pyramidology as unscriptural). Smyth's proposed dates for the Second Coming

The Second Coming (sometimes called the Second Advent or the Parousia) is a Christian (as well as Islamic and Baha'i) belief that Jesus will return again after his ascension to heaven about two thousand years ago. The idea is based on messi ...

, first 1882 then many dates between 1892 and 1911, were failed predictions.

The theories of Taylor and Smyth gained many eminent supporters and detractors in the field of Egyptology during the late 1800s, but by the end of the 19th century it had lost most of its mainstream scientific support. The greatest blow to the theory was dealt by the great Egyptogist William Matthew Flinders Petrie

Sir William Matthew Flinders Petrie ( – ), commonly known as simply Flinders Petrie, was a British Egyptologist and a pioneer of systematic methodology in archaeology and the preservation of artefacts. He held the first chair of Egypt ...

, who had initially been a supporter. When Petrie went to Egypt in 1880 to perform new measurements, he found that the pyramid was several feet smaller than previously believed. This so undermined the theory that Petrie rejected it, writing:"The theories of the widths and heights of the passages are all connected, as the passages are all of the same section, or multiples of that. The entrance passage height has had a curiously complex theory attached to it supposing that the vertical and perpendicular heights are added together, their sum is 100 so-called "Pyramid inches". This at the angle of 26º 31' would require a perpendicular height of 47.27, the actual height being 47.24 ± .02. But in considering any theory of the height of this passage, it can not be separated from the similar passages, or from the most accurately wrought of all such heights, the course height of the King's Chamber. The passages vary from 46.2 to 48.6, and the mean course height is 47.040 ± .013. So although this theory agrees with one of the passages, it is evidently not the origin of this frequently recurring height; and it is the more unlikely as there is no authentic example, that will bear examination, of the use or existence of any such measure as a "Pyramid inch," or of a cubit of 25.025 British inches."

Marriage, family, and death

In 1855 Smyth married Jessica "Jessie" Duncan (1812–1896), daughter of Thomas Duncan. Jessie Duncan was a geologist who had studied with Alexander Rose in Edinburgh, and travelled on geological expeditions to Ireland, France, Switzerland and Italy.

Smyth's brothers were

In 1855 Smyth married Jessica "Jessie" Duncan (1812–1896), daughter of Thomas Duncan. Jessie Duncan was a geologist who had studied with Alexander Rose in Edinburgh, and travelled on geological expeditions to Ireland, France, Switzerland and Italy.

Smyth's brothers were Warington Wilkinson Smyth

Sir Warington Wilkinson Smyth (26 August 181719 June 1890) was a British geologist.

Biography

Smyth was born at Naples, the son of Admiral W H Smyth and his wife Annarella Warington. His father was engaged in the Admiralty Survey of ...

and Henry Augustus Smyth

General Sir Henry Augustus Smyth (25 November 1825 – 19 September 1906) was a senior British Army officer. He was the son of Admiral William Henry Smyth and the brother of astronomer Charles Piazzi Smyth and geologist Sir Warington Wilkinso ...

. His sisters were Henrietta Grace Smyth, who married Reverend

The Reverend is an style (manner of address), honorific style most often placed before the names of Christian clergy and Minister of religion, ministers. There are sometimes differences in the way the style is used in different countries and c ...

Baden Powell and was mother of Robert Baden-Powell, 1st Baron Baden-Powell

Lieutenant-general (United Kingdom), Lieutenant-General Robert Stephenson Smyth Baden-Powell, 1st Baron Baden-Powell, ( ; (Commonly pronounced by others as ) 22 February 1857 – 8 January 1941) was a British Army officer, writer, foun ...

(founder of the world Scouting Movement

Scouting, also known as the Scout Movement, is a worldwide youth movement employing the Scout method, a program of informal education with an emphasis on practical outdoor activities, including camping, woodcraft, aquatics, hiking, backpacking ...

), Georgiana Rosetta Smyth, who married William Henry Flower

Sir William Henry Flower (30 November 18311 July 1899) was an English surgeon, museum curator and comparative anatomist, who became a leading authority on mammals and especially on the primate brain. He supported Thomas Henry Huxley in an imp ...

; and Ellen Philadelphia Smyth, who married Captain Henry Toynbee of the HEIC.

Smyth died in 1900 and was buried at St. John's Church in the village of Sharow near Ripon

Ripon () is a cathedral city in the Borough of Harrogate, North Yorkshire, England. The city is located at the confluence of two tributaries of the River Ure, the Laver and Skell. Historically part of the West Riding of Yorkshire, the city ...

. A small stone pyramid-shaped monument, topped by a Christian cross, marks his gravesite.

Honours

He was elected a Fellow of theRoyal Society of Edinburgh

The Royal Society of Edinburgh is Scotland's national academy of science and letters. It is a registered charity that operates on a wholly independent and non-partisan basis and provides public benefit throughout Scotland. It was established i ...

in 1846, and served on its council for a number of years. In June 1857 he was elected a Fellow of the Royal Society

Fellowship of the Royal Society (FRS, ForMemRS and HonFRS) is an award granted by the judges of the Royal Society of London to individuals who have made a "substantial contribution to the improvement of natural science, natural knowledge, incl ...

, but resigned in 1874. He was conferred with Honorary Membership of the Institution of Engineers and Shipbuilders in Scotland

The Institution of Engineers and Shipbuilders in Scotland (IESIS) is a multi-disciplinary professional body and learned society, founded in Scotland, for professional engineers in all disciplines and for those associated with or taking an interes ...

in 1859./ref> The crater Piazzi Smyth on the

moon

The Moon is Earth's only natural satellite. It is the fifth largest satellite in the Solar System and the largest and most massive relative to its parent planet, with a diameter about one-quarter that of Earth (comparable to the width of ...

is named after him.

Bibliography

*Full text available from

Google Books

Google Books (previously known as Google Book Search, Google Print, and by its code-name Project Ocean) is a service from Google Inc. that searches the full text of books and magazines that Google has scanned, converted to text using optical c ...

*

* Reprinted in many editions by many publishers, often entitled ''The Great Pyramid: Its Secrets and Mysteries Revealed''.Full text available

on the

Internet Archive

The Internet Archive is an American digital library with the stated mission of "universal access to all knowledge". It provides free public access to collections of digitized materials, including websites, software applications/games, music, ...

*Full text available from

Google Books *

Full text available from

Google Books * *

See also

*Geographical centre of Earth

The geographical center of Earth is the geometric center of all land surfaces on Earth. Geometrically defined it is the Centroid of all land surfaces within the two dimensions of the Geoid surface which approximates the Earth's outer shape. The ...

References

Critical comments

on some of Smyth's books, by Olin J. Eggen (1955). * * * *

External links

* * ttp://www.greatdreams.com/pyramid.htm Pyramidology – A Case of Science, Pseudo-science and Religion

Charles Piazzi Smyth, ''Our Inheritance in the Great Pyramid'' (1877) Plate Index

* ttp://www.catchpenny.org/pyramid.html Amazing Pyramid "Facts"

B-P's Uncle: Charles Piazzi Smyth

The Astronomical Society of Edinburgh: A Guide to Edinburgh's Popular Observatory

* ttp://www.leeds.ac.uk/cath/events/2003/1205/programme.html "The Sphinx and the Great Pyramid at Giza, 1865" photograph by Smyth

The Royal Observatory, Edinburgh

{{DEFAULTSORT:Smyth, Charles Piazzi 1819 births 1900 deaths 19th-century English writers 19th-century apocalypticists 19th-century writers on archaeological subjects Academics of the University of Edinburgh Alumni of the University of Edinburgh 19th-century British astronomers British Israelism 19th-century Neapolitan people Fellows of the Royal Astronomical Society Fellows of the Royal Society Fellows of the Royal Society of Edinburgh People educated at Bedford School Pyramidologists Victorian writers Great Pyramid of Giza